Jump to the section

Key Learnings

#1

Consensual Decision-Making

Inclusive and collaborative, this style values open dialogue and group alignment. Ideal for fostering trust, but it risks delays if consensus isn’t reached.

#2

Use Top-Down Efficiency when needed

Swift and decisive, this approach reflects authority and clarity. It drives quick action but may miss out on team input and engagement.

#3

Have Cultural Sensitivity and Adapt

Great leaders adapt their decision-making to fit cultural norms. They are balancing collaboration in collectivist settings and decisiveness in hierarchical ones.

#4

Use a Balanced Decision-Making

Combining team input with decisive leadership respects diverse perspectives while ensuring productivity and clarity in decision-making.

The Japanese systematically push a proposal through the ringi system, gathering input at each management level to build consensus. While Americans are accustomed to top-down decision-making, expect swift action and decisive leadership. The result? Tensions rise, misunderstandings abound, and progress stalls as cultural differences emerge.

Only a few decisions in leadership are one-size-fits-all. Consensual decision-making builds harmony and inclusiveness, depending on the input of all team members to reach a consensus. It’s the rule in cultures like Japan, which highly values consensus, or the Netherlands, where long discussions create shared decisions. On the other hand, top-down decisions reflect authority and efficiency. One key player-the leader-and leads decisions this method finds its niche in the United States and China, where clarity and decisiveness are core qualities.

Failure to recognize these divergent approaches can ignite friction. Team members from consensus-based cultures may be put off by strong leadership, while those from hierarchical systems often find consensus-building painfully slow. Such conflicts can destroy trust, reduce output, and derail progress.

The following article will help leaders bridge the gaps and explore “Big D vs. little d” decisions, share how to establish alignment in practical ways, and underline key ways to adapt your leadership style to different cultural norms, whether building consensus is your aim, making top-down decisions effectively, or a mix of both-using cultural awareness to unlock the power of your team. Let’s dive into how to lead across cultures with flair.

🌍 Consensual vs. Top-Down Decision-Making across Cultures

Consensual Decision-Making

Consensual decision-making is a collaborative process in which an agreement is reached on decisions through mutual input and consent. It thrives on open dialogue, thoughtful discussion, and a shared goal of finding solutions that satisfy everyone involved. At its core, it emphasizes building consensus to make sure every voice is heard and valued.

Where is Consensual Decision-Making Common?

This is deeply rooted in certain cultural contexts. In Japan, the ringi system way proposals travel up the hierarchy for approval-illuminates this, and at each level, this builds collective ownership. Similarly, Sweden’s focus on egalitarianism shapes its open dialogue culture, where equal participation is encouraged. In the Netherlands, often debates happen publicly, underlining the transparency and accountability of decision-making. Each of these practices reflects the cultural values of collectivism, harmony, and equality characteristic of these countries.

Consensual Decision-Making Advantages

Large groups of leaders often view the consensual decision-making process as favorable. This includes increased buy-in because “team members are likely to commit to the result of a process where they have felt heard.” This captures a diverse perspective, thus creative and well-rounded solutions merge with all types of insights. Beyond the results, the process strengthens relationships between a team with the building of stronger cohesion.

Challenges of Consensual Decision-Making

This approach, however, is not without any challenges. Slower decision-making frustrates the teams most when time is of the essence. Conflicting opinions may result in deadlocks that stall progress. Besides, this urge for harmony may at times force groupthink, and suppress the dissident views, often at the cost of the quality of the decision.

Real-World Examples in Consensual Decision-Making

Real-life examples are replete with these dynamics. The Japanese ringi system ensures that all stakeholders approve proposals before implementation, creating alignment and accountability. In Dutch organizations, public debates build trust and transparency. Swedish companies emphasize egalitarianism by fostering inclusive participation during decision-making.

In such a setting, the leader has to develop his approach to get along with the cultural differences. The openness in communication ensures that all opinions have been expressed. Understanding is achieved by listening and summarizing. The decision-making is strengthened by opening the floor for respectful disagreement. Leaders seek consensus, not unanimity, so they can move ahead even if some minor reservations linger. Finally, clear definitions at the outset regarding how decisions will be made establish clarity and set expectations.

Top-Down Decision-Making

Top-down decision-making puts responsibility for decisions at the top of an organization’s hierarchy; leaders, executives, or managers make decisions, with limited input from others; the emphasis is on efficiency and clear accountability. This style thrives in organizations where well-defined hierarchies and chains of command ensure smooth implementation and streamlined communication.

Cultural Contexts of Top-Down Decision-Making

The prevalence of top-down decisions can often be a reflection of the cultural values of a region. Efficiency and individualism are the drives of this style in the United States. Decisions are seen more as flexible and dynamic, or “little d” decisions, that are always subject to change with new developments. In China, the hierarchical values of respect for authority and seniority make sure that decision-making stays centralized. In France, the strong value placed on strong leadership thus means that a decisive approach, giving direction with little ambiguity, is favored.

Advantages of a Top-Down Approach

One of the major advantages of top-down decisions is efficiency. The leaders can make fast decisions without taking a lot of time for consultations, priceless in a fast-moving environment or under pressure. Another benefit is clarity of direction since a clearly defined chain of command diminishes uncertainty, hence the team members can focus on the execution part. Moreover, accountability is clear; it is easy to identify who made a certain decision and thus credit or blame can easily be given, which may elevate the quality of decisions.

Drawbacks of Top Down Approach

While strong, this has several limitations. This system denies the decision makers some of the useful ideas from team members. The most frequent scenario, though, is the less-than-ideal decision that is unable to incorporate realities on the ground. Also, the members will feel belittled and left out, thus being resentful and noncommittal to seeing decisions through. In such situations, a blend between the authority centralized and the opportunity for input and feedback should be struck.

Real-World Examples in Top-Down Decision-Making

The approach of top-down decision-making applies to military organizations. Such leaders often need to make split-second decisions, particularly where their decision may mean life and death. Crisis management has a good role in this regard as top-down decision-making will give more control over natural catastrophes or product recall actions. Early-stage ventures in highly competitive businesses, where speed-to-market plays an important role, adopt the top-down leadership of managers.

Consensual vs. Top-Down Decision-Making

| Aspect | Consensual Decision-Making | Top-Down Decision-Making |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Decisions are made collectively with input from all team members, aiming for unanimous agreement. | Decisions are made by individuals in authority, often with limited input from others. |

| Cultural Alignment | Common in Japan, Sweden, the Netherlands, and other cultures valuing harmony and collaboration. | Prevalent in the United States, China, France, and hierarchical cultures valuing authority and efficiency. |

| Key Characteristics | – Collaboration and inclusivity. | – Authority-driven. |

| – Extensive discussions to explore diverse perspectives. | – Quick decision-making prioritizing speed. | |

| – Implementation occurs swiftly once consensus is reached. | – Decisions are flexible and can be revised if necessary. | |

| Advantages | – Encourages diverse perspectives, fostering innovation. | – Ensures efficiency and clarity of direction. |

| – Builds team cohesion and trust. | – Assigns clear accountability to decision-makers. | |

| – Increases buy-in and commitment from team members. | – Reduces delays in urgent or high-stakes situations. | |

| Disadvantages | – Decision-making can be slow, especially in large groups or complex scenarios. | – May overlook valuable input from team members closer to the ground. |

| – Risk of deadlock if opposing views prevent agreement. | – Can lead to resentment or disengagement if team members feel excluded. | |

| – Potential for groupthink, stifling dissent and critical evaluation. | – Decisions made in isolation may fail to address practical challenges. | |

| Examples | – Japanese Ringi System: Proposals are circulated and approved at various levels before finalization. | – Military: High-stakes operations require rapid, authoritative decisions. |

| – Dutch Public Consensus: Open debates ensure transparency and collective agreement. | – Start-Ups: Founders often make centralized decisions to maintain agility in fast-moving industries. | |

| – Swedish Egalitarianism: Equal participation and open dialogue guide the decision-making process. | – Crisis Management: Top-down decisions ensure coordinated responses during emergencies. | |

| Leadership Strategies | – Foster open communication and active listening. | – Communicate the rationale behind decisions to build understanding. |

| – Encourage constructive disagreements to avoid groupthink. | – Seek input strategically to gather insights while retaining decision-making authority. | |

| – Define the decision-making process upfront to manage expectations. | – Empower team members through delegation and encourage feedback for refinement. |

The Culture Map: A Framework for Decision-Making Styles

In The Culture Map, Erin Meyer has given the needed tools for managing cross-cultural differences in business. The tool allows leaders to view and work out how cultures vary from one another on eight dimensions. One of these is “Deciding.” After much research, Meyer has presented a culture map with pragmatic approaches that will increase cross-cultural collaboration, which is imperative for every leader willing to deal effectively with cultural differences.

The “Deciding” Scale: From Consensus to Authority

The “Deciding” scale lies at the heart of the Culture Map, underlining the range of decision-making styles: on one extreme, consensual decision-making emphasizes collective agreement with a say from all team members; on the opposite extreme, top-down decisions are made unilaterally by leaders in an authoritative manner. Although referred to as “Consensual” and “Unilateral” by some, other sources refer to these styles as “Consensus-Based” and “Directive,” respectively. Whatever the terms used, the dynamics remain the same.

Cultural Contexts Along the Scale

Countries tend to differ in their tendencies along the “Deciding” scale. Consensual cultures, such as Japan, Sweden, and the Netherlands, tend to make decisions based on collective agreement. However, the process differs; in Japan, consensus-building tends to occur privately, while in the Netherlands, debates are more public. Germany combines a formal workplace hierarchy with significant input from technical experts, blending elements of both styles.

In top-down cultures, such as the United States, China, and France, decisions move quickly and centrally. Despite the flat organizations of the United States, it focuses on rapid efficiency and adaptability with decisions. Respect for both hierarchy and authority in China guides and shapes decision-making. The French require clear direction and strong, decisive leadership in the workplace.

Value of the Culture Map for Anticipating Challenges

Understanding the “Deciding” scale equips the leader to anticipate challenges in multicultural teams. Conflicting expectations abound. Team members from consensual cultures may consider top-down approaches abrupt, while those from top-down cultures may view consensus-building as an ineffective use of time. Communications break down; in high-context cultures, for example, silence may signal disapproval, which may be misinterpreted by low-context cultures as assent. In the absence of a clear process, delays and frustrations erode team progress.

Strategies for Bridging Cultural Differences

Leaders can take steps to encourage collaboration across cultural divides. Discussing preferences for decision-making upfront ensures mutual understanding. Coming to a consensus on a hybrid decision-making process, combining consensus-based and top-down approaches, can also work. Creating “third-culture” norms, where the different perspectives are melded together, helps bridge differences. Building trust and relationships fosters an environment for open communication. Clear language and visuals can further minimize misinterpretation, especially in teams combining high-context and low-context cultures. Patience and flexibility are key as teams learn to align their approaches.

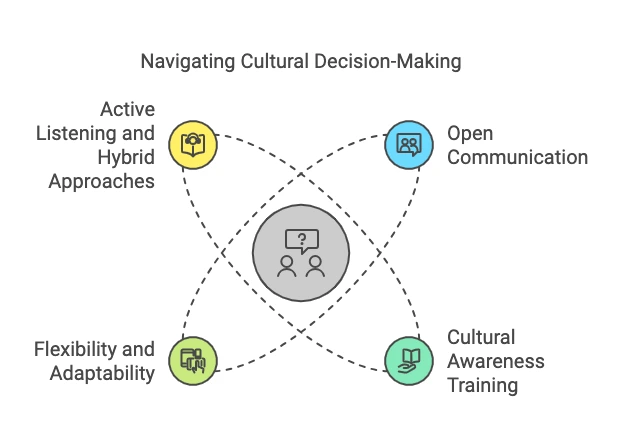

How to Decide Through Cultural Differences?

Effective leaders recognize that there is no single way to make a decision, especially in multicultural teams. To manage cultural differences, strategies are necessary that can balance consensual decision-making with top-down decisions so that all voices are valued, but clear leadership is maintained.

Open Communication and Clear Expectations

Open communication is the foundation of effective leadership in multicultural teams. The leader must provide an environment in which the team members can share their preferred ways of decision-making. Setting the rules and expectations beforehand leaves very little room for misunderstanding. Decision-making training and some role-playing exercises can make working with different styles quite seamless. Adaptable policies in decision-making balance out the building of consensus against the authority of the leader to promote openness and inclusion. Discussion guides to the cultural norms allow the team to learn about other teammates’ ways.

Cultural Awareness Training

Leaders should prepare their teams by giving them tools that outline cultural considerations when making decisions. Books such as The Culture Map by Erin Meyer and When Cultures Collide by Richard D. Lewis give a perspective into how culture informs leadership styles, communication, and decisions. Training programs on the differing concepts of hierarchy, authority, and collaboration open the minds of team members toward the differences and help in engendering mutual respect.

Flexibility and Adaptability

The style of the leader needs to adjust to fit the cultural environment of his team. For instance, top-down decisions are expected in hierarchical cultures, and one may need to make claims of authority more assertive. The leader should be patient with the longer discussions and facilitate group input in consensus-driven atmospheres. Changing the behaviors of leaders-for example, one-on-one discussions in hierarchical settings and encouragement of group collaboration in egalitarian cultures are bridged.

Active Listening and Hybrid Approaches

Active listening is important both in consensus and top-down situations. In consensus cultures, leaders must be patient and much more committed to group deliberation. In top-down systems, leaders solicit opinions from their staff and then make the decision. Combining the two styles-soliciting input from the team but reserving the right to make a final decision a hybrid style that maximizes the efficiencies of both processes.

Decision-Making using Cultural Diversity

In the modern, multicultural world, effective leadership determines how well an organization can manage cultural differences in decision-making. By better understanding how to balance consensual and top-down decisions, one can build trust, unleash creativity, and guarantee success.

Frameworks such as The Culture Map arm the manager to know how to lead around such cultural nuances, showing how decision-making styles vary across cultures: in consensus-driven cultures like Japan and the Netherlands, collaboration comes first; in the U.S. and China, top-down decisions, a priority on efficiency, rule. Being able to identify and adapt to these preferences makes it easier for leaders to realize any forthcoming barriers and close expectation gaps.

The most effective leaders adopt a flexible approach, blending the collaborative and authoritative styles to suit the cultural context of the team. This may be achieved through open communication, cultural awareness training, or hybrid approaches that make for inclusive environments for diverse perspectives.

Cultural diversity is not a problem but an asset. Where leaders link their decision-making practice with consideration of culture, they develop teams that can solve complex problems innovatively and deliver superior results.

FAQs

Consensual decision-making involves input from all team members to reach a collective agreement, emphasizing collaboration and inclusivity. Top-down decision-making places authority with leaders, focusing on efficiency and clarity, often with limited team input.

Cultural norms play a significant role in decision-making. For instance, Japan and Sweden prefer consensus-building due to values of harmony and collaboration, while the U.S. and China favor top-down decisions for their focus on authority and efficiency.

The Culture Map is a framework that identifies and explains cultural differences across eight dimensions, including decision-making. It helps leaders understand how to adapt their leadership styles for multicultural teams.

Leaders can use strategies like open communication, cultural awareness training, and hybrid approaches that blend consensual and top-down methods to align diverse teams and foster collaboration.

Cultural diversity brings varied perspectives, enhancing creativity and innovation. Leaders who embrace cultural differences build inclusive teams capable of solving complex challenges effectively.